"We need our farmers to be artists and our artists to be farmers" — Nick Hayes and Emma Kernahan at NeoAncients

by Roma Robinson | The RYSE

May 2025

“We need our farmers to be artists and our artists to be farmers” – Nick Hayes and Emma Kernahan on trespass, community ownership and litter picking.

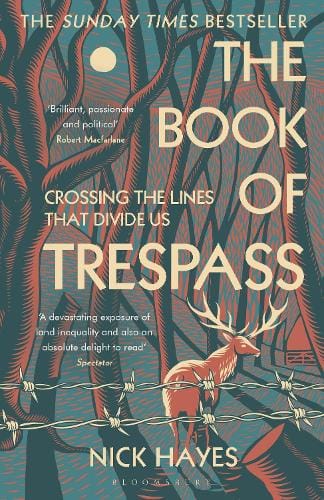

Nick Hayes is the author and co-founder of the Right to Roam campaign, and it was his book, The Book of Trespass, that my mum recommended to me about four years ago.

I devoured it.

It’s part history, part political, part nature diary, and spans several centuries of land rights in the UK, and this potent mixture of topics and styles is what I enjoy and made reading it feel as easy as a glass of cold water on a hot day. Reading this book was another politicising moment for me on the journey I’m still walking to understand the world and how we got to this knife edge point in our story.

He describes himself as “like Robert Macfarlane with a socialist stick up his ass.”

And Emma? I just think Emma’s lush. Writer, universal basic income campaigner, and all round good egg.

I first got to know her – serendipitously – a year ago when we were paired up covering the last NeoAncients festival for Amplify Stroud. Since then I’ve been part of the Dialect rural writers group she runs. It’s always a privilege to see her do her thing.

The venue, Lansdowne Hall, is packed and the talk starts a little late to give the last stragglers time to filter in and make themselves at home wherever there’s a spot.

Between Emma’s down to earth humour and Nick’s relaxed and impish charisma, it’s a highly entertaining and informative hour. There’s no pretentiousness here, and I was immediately drawn to the way that Nick talks about the outdoors.

It was my mum singing at a local festival of less than 400 people in a slightly mouldy marquee in the shadow of Berkeley nuclear power station.

It was my nan roping 6-year-old me into pricing products at the village store because they didn’t have enough staff – if you were overcharged at Nibley Stores 15 years ago, I’m sorry, that was probably my bad.

There is a very romanticised view of rural areas, Emma puts it as “children wearing beige next to cow parsley in the sun.

“They forget about the village Spar.”

Among some older people there is a distrust of teenagers spending time in nature, drinking or having fires because of the dreaded ‘L’ word.

Litter

Many a facebook post has been made decrying the horrors of littering in our fields and woods. On one particularly memorable occasion I saw someone post a picture of a whole sofa, dragged at least a mile from the nearest road.

But Nick says that this shouldn’t mean condemnation, or loss of access. Although there is some resentment among litter pickers, he stresses that community is hard work.

He’s right, a conservative land access that strictly tells us who and who doesn’t deserve to be here is no land access at all. And it won’t teach responsibility.

Emma said: “Give people the space to understand that we are all in it together and that if you fuck up you might get a bollocking but there isn’t a forever shame attached to mistakes.

“There’s a compassion there, and we need it.”

With the successful community land purchase of Thrupp Farm - known locally at the Heavens - a few months ago, that balance has got to be a very live conversation within Stroud.

The 102-acre site is a beloved walking and beauty spot where a huge cross section of the community goes. It went up for sale a year ago, threatening the access that we have enjoyed for decades, and a community group “Save the Heavens” bought the site over the winter.

It’s a step towards land justice in Stroud after several decades of Micro-Enclosure – where land access is slowly chipped away by land owners adding an extra fence here, ploughing over a public footpath there and generally decreasing access to land.

Much of the land around Stroud has access enshrined in the Cotswold way, but ultimately it isn’t Land Justice. The King’s estate still takes up 1000 acres of our land, I was still chased from fields as a child, and most people still don’t have enough access to gardening space.

Community members can purchase a £50 share in the site, bringing it into community ownership, and are able to vote on the way the land is used. The project is blossoming into itself, running consultations and public meetings to decide what to do with this community asset.

This is one way of saving land for community use.

But Nick highlights more unorthodox ways.

In November 2022, the Esme Boggart art collective, of which Nick is a member, helped resist a no fault eviction of a family of seven from the house they’d lived in for 26 years on the Mapledurham estate in Oxfordshire.

Esme Boggart is a silt witch, a mythological figure called through for this eviction, and then burnt.

An action group taking on a collective pseudonym is reminiscent of the Rebecca Riots, where land workers protested taxation dressed as women, taking the name Merched Beca, which translates from Welsh to “Rebecca’s daughters”.

Nick:

“Direct action is when you do something interesting in a hard to ignore way. They might have all of the acres but we have all the songs.”

Nick:

“it must be quite crushing for the land owner to realise they’re the least important part of [the land]. They’re the most distant part of the estate.

“We’re having a lot more fun than them.”

The Esme Boggart effigy was at the centre of a festival that took place the day the eviction was due, and it took something destabilising and turned it into something generative and joyful. This is a story that Stroud, and the Heavens knows well.

Also on stage, to Emma’s right sits the 4-foot-something puppet of the Spirit of the Heavens, made and designed by artist Alison Cockcroft and inspired by Esme. This wicker sculpture is admittedly slightly shorter than the silt witch and was part of a poetry fundraiser evening hosted in the cosy Trinity Rooms in November raising the Spirit of the Heavens.

The comparison between these two campaigns certainly raises an interesting question about tactics – the out and out eviction resistance on the Mapledurham estate seen next to the community land purchase of the Heavens.

Emma walks her dog most days in the Heavens, and organised the Raising the Spirit fundraiser, reflects on her relationship to the farm:

“Where I walked before, now I feel belonging and the feeling of my responsibility to it has completely changed.”

When fundraising for the Heavens was still ongoing, I can remember feeling the dissonance as I saw the amount of money they were able to raise go up and up, while I saw Gofundmes for Palestinian families falter, families within Stroud continue to suffer under the cost of living crisis and homeless people on the street.

I heard that at one of the Heaven’s fundraisers, someone casually showed up and made a donation for £15,000.

The Heavens was purchased for £850,000, £300,000 of it through community donations. The remaining £550,000 was raised through two loans from community members.

I can remember the public meeting I went to a little after it was confirmed that they had raised enough money, the feeling of being a bit split between gratitude for the work that had gone in to save the area, and sadness that it had been so possible to raise such an incredible amount of money while other causes go without.

Talking to Emma after the event, she echoed this sentiment. She had worked as a housing and financial support worker for over a decade, and over the COVID pandemic, every day seeing cases with families who were being asked to chose between things like a fridge, a freezer or a washing machine because the council wouldn’t fund all three.

Her job was getting them the support, and she knows first hand how people will ignore this.

I couldn’t help thinking that this money have gone to rescue or feed a family from Gaza, or towards a community mutual aid fund to make sure no one in Stroud goes hungry or cold. And when funds are set up for these things, who will prioritise them over a patch of land? Why can’t they raise almost a million pounds in three months?

In general, I think this response of what-about-ism is generally unhelpful, and as someone who has spent a lot of time in the Heavens I am very grateful that this purchase was able to happen.

But I’m also curious about how we can justify our massive collective resources, which we only have because we live in an affluent part of the imperial core, going towards something when other tactics are available to us to secure land justice?

But the family on the Mapledurham estate were evicted.

In one definition of the word, Esme Boggart failed where the Heavens succeeded, through one tactic the land was lost, through another it’s been brought into community ownership.

In another definition, they succeed to show a family that they were loved by their community, who would show up for them.

I’m not here to come down on one side or another right now. I don’t even think you can class one or the other as a success or a failure, and Emma makes a beautiful point on this:

“I never thought [Esme Boggart] was gonna win this. And that’s what made it so powerful to me - you don’t go down without a fight. And that’s also what all the housing support workers are doing, they aren’t going down without a fight.

“And when we saw [Esme Boggart], it gave us hope. They were doing the action we didn’t have capacity to do.

From sinking and surviving, to power building and thriving

The primary other issue that they touched on was Universal Basic Income (UBI) – and Emma, as a co-founder of the Stroud UBI lab, was well prepared.

UBI is a regular guaranteed payment to everyone, giving people a solid basis to build the rest of their lives on. You can read Emma’s own explanation of what UBI is and why it’s right for Stroud here.

Her time as a housing support worker clearly demonstrated the failings of a system that wasn’t looking after people. Having a clear consistent income safety net could give people the space to do more than just scrape by, it could give people a feeling of security that allows them to build and thrive.

And Nick brings his artist’s perspective to the conversation, and says that although he spends much of his time campaigning for a Right to Roam, between Right to Roam and UBI – we need UBI.

“We used to have more time to look after each other.”

And for Nick UBI also speaks to communities working together, and gives people the breathing space they need to be well rounded: “We need our farmers to be artists and our artists to be farmers.”

I went to see Three Acres and a Cow – also in Lansdowne hall – a little under three years ago. Robin Grey, the musician behind it, made a tongue in cheek remark that I actually think about a lot.

Real three acres and a cow fans know that the name comes from an 1880s slogan which stated every adult be given – that’s right – smallholdings consisting of three acres and a cow to ensure that they could grow their own food and have dairy products.

We could look after each other if we had access to our own land, if we had a universal basic guarantee of survival and the materials needed for survival.

We need land, we need access to land and we need to build power on and with the land, because while the capitalists control the flow of resources we’ll always be reliant on them, and on the race-to-the-bottom mistreatment of our siblings in the Global South.

If we understand that we need land, and that in order to get that land we need to use a variety of tactics at our disposal, we can in turn be pulled into a shared fight with others fighting for the same things.

From the Palestinian right of return, the Zapatista’s autonomous zone, the AES’s pan-afrikan reimagination of their identity, an end to the enclosures in England and a right to the land - we all need the same thing.

And we need to work together.

Roma Robinson is a member of the RYSE (Radical Youth Space for Educations).

Amplify Stroud is supported by Dialect rural writers collective. Dialect offers mentorship, encouragement and self-study courses as well as publishing.

You can find out more at https://www.dialect.org.uk/

Member discussion