Stroud, Slavery and the misremembering of William Wilberforce

By Jamie O’Dell and George D Thomas

With the country’s oldest memorial to the abolition of the slave trade, Stroud has a unique and often quite proud relationship with the abolitionist movement. In the months before Coronavirus hit the UK, we at Amplify Stroud were working in collaboration with Stuart Butler of Radical Stroud; to uncover the hidden truths of our town’s colonial history.

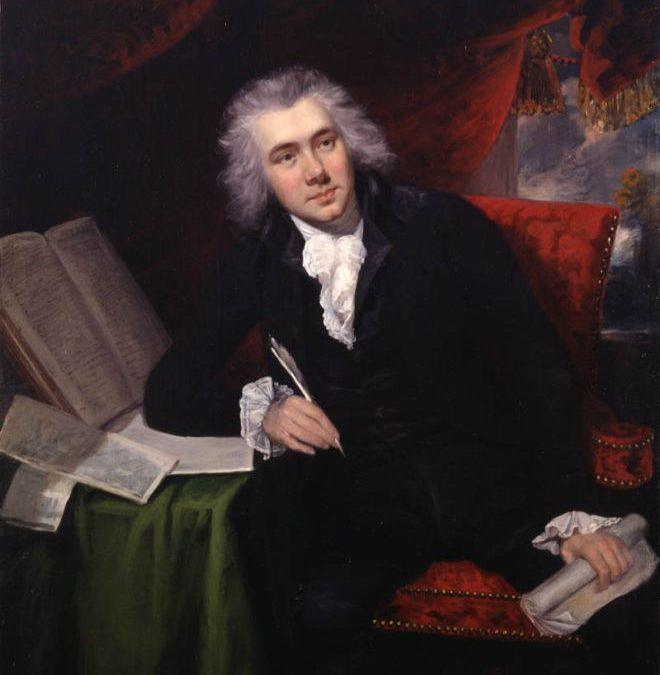

Yesterday, May 12th, marked the 231st anniversary of celebrated abolitionist William Wilberforce’s first major speech on abolition in the House of Commons. So we thought it a suitable opportunity to briefly share some of our initial findings and discuss their importance.

Wilberforce himself was born in Hull in 1759, and is remembered as the pious parliamentary spokesman for the abolitionist movement. However, as happens all too often when we look back on the darker parts of our nation’s history, his moralising image is present when the names and faces of those who suffered under British imperialism are erased almost entirely.

Now, it is indeed true that the national efforts of Wilberforce (amongst others, such as Glanville Sharp) were key in rendering this barbaric practice, responsible for the kidnap and transportation of an estimated 10-12 million people from the African continent, illegal. Unless we cast a sharper, more critical eye over these easy narratives of social justice, however, we fail to truly and honestly understand our history and culture.

Stroud was also home to proponents of abolitionist sentiment, including Henry Wyatt, the member of the Stroud Anti-Slavery Society who funded the construction of the Anti-Slavery Arch (photo above) on the edge of what is now the Paganhill Estate in 1834. Despite being unique in the country, and being one of our town’s only symbols of the British Empire’s slavery and wider colonial project, the Grade II* listed monument isn’t even listed on Google Maps. Furthermore, rather than existing purely as the sole public memorial to the enslavement of millions, in its day the arch was also the grand entrance to Wyatt’s Georgian mansion.

It must be remembered that in 1834, alongside the enactment of Britain’s new laws against owning other human beings, there came bailouts for slave owners. With many individuals in towns such as Stroud benefitting from a cash injection, the likes of which our nation had never seen before. If these facts of Stroud’s connection to Britain’s colonial project are so easily forgotten, these physical locations and personal histories are often all that consciously connects us to this practice.

This represents a fundamental and quite purposeful mis-remembering of the slave trade. One that allows us to spin centuries of savage exploitation into a positive moment of British Civilisation, one of virtue, morality, justice. Furthermore, it paints a very narrow, and very white, picture of saviourism and abolition. After all, we were the first to abolish it…

In his 2018 book ‘Natives’, musician and author Akala, references the time when, at 7 years old and on a school trip to the National Portrait Gallery, his school teacher stood him in front of a painting of, and I quote, ‘Mr William – patron saint of black emancipation – Wilberforce’.

“‘Kingslee…this man stopped slavery’…’What, all by himself, miss?’ I asked. ‘Don’t you mean he helped?’…’No Kingslee, he stopped slavery,’ she retorted, clearly annoyed at my refusal to blindly accept what I was being told.”

This extract highlights not just the centralisation of Wilberforce in our popular narratives on the chattel-slavery of people from the African continent, but also the way in which we seek to find a sense of national pride in ending a cruel business we ought never to have entered.

Through centralising a white actor, it marginalises and ignores the significant impact and agency of black people in ending the practice themselves. For instance, black British abolitionists living and campaigning in England at the time, such as Olaudah Equiano, Toussaint L’Ouverture, the Haitian who led the first successful slave revolution since Spartacus, or Solitude, a woman who was executed by French forces for her role in leading, whilst pregnant, a Maroon revolt in Guadalupe. Even the strikes in 1862 by ordinary British mill workers in Manchester, in an act of solidarity with the slaves who picked the cotton they weaved, are outshone by the legend of Wilberforce. All these being people who, quite frankly, risked more and sacrificed more for the cause of emancipation.

To return to Akala, he neatly summarised the ‘self-serving fairy tale that suddenly, in 1807* – just three years after Haitian independence – guided by William Wilberforce alone, Britain abolished slavery because it was ‘the right thing to do’ as ‘a pile of twaddle’.

This misremembering thus serves to rewrite and whitewash our own relationship with the slave trade and consequently enables us to ignore the legacies of it which we still live with today. In Stroud, for instance, Stuart Butler has lifted the lid on the scale and extent of slave ownership in the local area. Using records made publicly available by University College London, of slave owners who were compensated by the British state for their loss of ‘property’ (no one thinking to compensate the actual slaves for being ‘property’), Butler has also brought the names of some of these slave owners to light. Such as;

- Samuel Baker, of Lypiatt Park, who owned 410 slaves in Jamaica and was paid £7,990.

- John Clarke, of Frocester Estate, who owned 482 slaves in Jamaica and was paid £3,879 and 3 shillings.

- Mary Lindesey, of Minchinhampton, who owned 276 slaves in Antigua and was paid £4,194 12 shillings and 7 pence.

- Rev. Joseph Ostrehan, of Sheepscombe Parsonage, who owned 3 slaves in Barbados and received £858 and 8 shillings.

When adjusting for inflation, £1,000 in 1833 is the equivalent to £120,000 in 2019, meaning that Samuel Baker was compensated to the tune of £958,211.20 when adjusted for inflation, with this amount having an economic share of GDP equivalent to £38,900,000 in today’s money. That’s almost exactly £95,000 per person.

These are vast sums of money, reflecting the economic value and importance of plantation slavery for the British and European economies and economic development. Development we still benefit from today.

Slavery has given us more than just this economic development, however. It was also built upon and justified through the development of racism. Racism here is a specifically designed system and hierarchy of power constructed to segregate black from white upon supposed biological lines in order to justify the horrific conditions and exploitations of chattel slavery. It is worth, at this point, remembering that these conditions were alive and kicking in British territories 187 years ago.

The divisions structured into the world then are still very much the divisions that we live with today on a global and a national level. We only need to look at the disproportionate global impact of the climate emergency, or the harrowing fact that black people in the UK are four times more likely to die from Coronavirus than whites, to see the impact of the structural racism.

Therefore, it is crucial that nationally, and within Stroud, we recalibrate who we remember when discussing the Transatlantic Slave Trade. That we recognise the extent to which the physical and social spaces we inhabit are directly built upon this. Finally, that we consequently consider, as the matter of life and death it so obviously is, the conscious and constant steps that we must take as a society to recognise and undo the racism so prevalent in all of our everyday lives.

*The slave trade, was abolished in 1807, but the act of owning slaves in British overseas territories was not abolished until 1833, and even then the ensuing employment practices represented little change for many.

Member discussion