Requiem for Protest? A response

David Lambert | Writer

November 2025

Since July 2023, Defend our Juries (DoJ) has been campaigning to protect the right of jurors to deliver a verdict according to their conscience.

Since July 2025 that campaign has extended into Lift the Ban, seeking to persuade the government to reverse its proscription of Palestine Action under the Terrorism Act 2000.

DoJ has been organising monthly actions in Parliament Square and Trafalgar Square, in which people sit silently with a placard stating the words: “I Oppose Genocide I Support Palestine Action.”

Under the terms of that proscription, the last four words constitute a breach of the Terrorism Act. So far over two thousand people, mostly over the age of sixty, have been arrested, including over twenty from Stroud.

The world’s media has been flooded with images of pensioners, clerics, ex-military, even people in wheelchairs, being escorted or carried off by police officers as terror suspects.

After the action on 4 October, where a further 488 people were arrested in Trafalgar Square, a short film directed by Liz Smith of the team at Page 75 Investigates, was released on YouTube, entitled Requiem for Protest.

Over images of the October action, it narrates the dismal story of the UK state’s recent repression of dissent, from Parliamentary debates in 1999 over the Terrorism bill, through the seemingly endless sequence of extensions to police powers to prevent protests, to the crackdown on DoJ and the latest Home Secretary’s plan to outlaw repeat protests.

It is a powerful film, punctuated by politicians’ sanctimonious assurances that the right to protest is fundamental to our democracy.

Nothing could illustrate better the way in which the crackdown on effective protest is not a political choice but one driven by the state as a whole – the non-political actors behind the ever-changing cast of ministers.

We talk about a ‘right to protest’ as if it were fundamental to western democracy.

The right to free speech and free assembly are both enshrined in the 1953 European Convention on Human Rights, subsequently brought into UK law in the 1998 Human Rights Act.

It is worth bearing in mind how recent both these pieces of legislation are. And in addition, a cynic might argue that the much-vaunted right to protest is not the same as a right to effective protest.

From Peterloo to Orgreave, via Captain Swing and the Suffragette movement, you could argue that effective protest invariably elicits a powerful, often violent, counter-force.

The last twenty-five years have seen a similarly repressive reaction to protest around anti-capitalism, Black Lives Matter, climate and now Palestine.

Protest will continue. 600,000 people marched through central London on the 11 October in support of Palestine. No doubt many hundreds, or thousands, more will invite arrest in support of lifting the ban on Palestine Action. So in a sense the title of the film was melodramatic; it was still a call to action rather than a requiem.

This reminds me of the words of the Nigerian thinker, Bayo Akomolafe, who calls himself a post-activist and who questions western paradigms of activism, of solutions (he calls it solutionism), of hope, of progress.

He notes that in many instances, protests reproduce the very paradigms that are the object of protest.

He has observed that the rush to act often results in unforeseen consequences, that “doing something” often does something else entirely; that the fire we seek to extinguish ‘might grow on the oxygen of our most earnest gestures’; that ‘the compulsion to act may itself be the residue of a theology desperate to place humans at the centre of consequence.

Here in the west we inhabit the project of modernity, ushered in by the seventeenth century European ‘Enlightenment’ and its faith in causality and agency.

Just as micro-plastics are in our lungs and brains, so individualism, technocracy, consumerism, and ongoing colonialism are metaphorically in the air we breathe in our activism: ‘Yes We Can; You Can Make a Difference; If not You Who; If not Now When’.

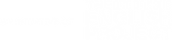

Perhaps our protests, far from bringing down a toxic system, actually play a part in its survival. It is possible to look at the last twenty-five years and conclude that protest has not only failed to bring about change but also ushered in greater repression.

Maybe our hopefulness needs to be interrogated: as another thinker, Gruff Rhys lead singer in the band Super Furry Animals, says: ‘hope and joy are becoming imperialist constructs… maybe sadness can empower us.’

So maybe the way we see the problem is part of the problem.

Or as Dougald Hine puts it, we need to recognise that what we face in the unravelling of modernity is not a problem at all but a predicament: not something outside us, to be fixed, but rather, something we are in and which is within us: something in which we are entangled.

Perhaps we need to acknowledge the limits of our agency over the forces that are now shaking us to our core.

Protest will continue but within ever stricter boundaries, with ever fiercer punishment for transgressing those boundaries.

Not only are police powers increasing, access to justice is reducing; the government is seriously considering the Leveson report which in July recommended a major reduction in access to jury trials.

Another twenty-five years could see an end to mass public protests. Opposition will never die but dissenters will learn to live with fear and control and punishment.

But this is not to say we are helpless. Love and joy survive slavery; community survives oppression.

As many activists have said, ‘You bury me but I am a seed’. In losing our way, we can find it. In subjugation, we can learn other ways of being, other ways of relating to the world.

As in so many places in space and time, throughout the world and throughout history, community, relationships, and a vibrant, fecund, life-affirming underground will always survive.

We in the west have lessons to learn.

And from Africa: the submergence of the individual in the greater community contained in the concept of Ubuntu – “I am I only because We are We.”

No testimony from Gaza has moved me more than an interview with Dr Ghassan Abu-Sittah in December 2023, when after bearing witness to the suffering of the innocent and the brutality of the oppressors, he is asked one last question: where are you anchoring hope?

To which he replies, and it sounds unhesitating, ‘Oh, in Gaza. Absolutely.’

David Lambert is a Stroud resident and former Extinction Rebel.

Amplify Stroud is supported by Dialect rural writers collective. Dialect offers mentorship, encouragement and self-study courses as well as publishing.

You can find out more at https://www.dialect.org.uk/

Member discussion