Gleaning in: Cooking up the Future in the Stroud Valleys

Words and Photos by Emma Kernahan | Dialect

September 2025

It’s 1.30pm on a hot summer Saturday, and Stroud’s farmer’s market is packing up. It’s been a typically busy morning and the lanes off the high street are still crowded with locals, and holidaymakers venturing beyond the coach tour end of the Cotswolds.

In other places, surplus like this would be composted, fed to animals or binned, forming part of the 4.5 million tonnes of edible food waste created by the UK annually. (Waste Direct 2025).

In the UK, a whopping 9 million tonnes of food in total is wasted each year, enough to feed 30 million people - and costing us £19 billion annually. But in Stroud, at Saturday lunch time, something unusual springs into action - a unique and finely honed food redistribution system, taking local unused produce and redirecting it, not just to a single community space, but to people all over town.

This system is overseen by The Trinity Rooms - a central hub in the old residential part of Stroud. The building itself is an unassuming Victorian red brick hall, run for over a century by the nearby Holy Trinity Church.

But in the five years since its management was taken over by Stroud Earth Community, it’s become home to everything from political meetings, music events, fundraisers and writing retreats, to gong baths, repair cafes and their word of mouth phenomenon, the Friday community cafe.

A fundraising campaign was launched in 2024 to bring the Trinity Rooms into community ownership for good - the latest in a flurry of such campaigns locally.

Today, I’m here to join the Trinity Rooms volunteers on their food collection from the market.

From its early beginnings as an exchange between the Trinity Rooms and the market, the surplus gathering system has grown into something that includes local growers and producers beyond the market itself, as well as high street shops such as Greggs in the town centre - connecting their leftover produce with NoSH - the Network of Stroud Hubs, which is a network of 6 community pantries and hubs around Stroud.

I meet the volunteers outside Iceland, in the heart of the market. Once we have the trolley that Iceland lend the group each week, they weave through the crowd with well-practiced speed.

There is a narrow window for collection - too early and the stall holders will be looking to make the most of the last minute sales, too late and they’ll have already packed up. There are people waiting back at the Trinity Rooms for the food - so we don’t hang about.

The volunteers are well known to the stall holders, and as soon as the trolley is spotted, I can see food being bagged up ready for handing over. Swift and capable as the process is, there’s an ease to it - volunteers, stall holders and passing customers know each other by sight, and the giving and receiving feels natural and unpressured.

“Some people might say they hope to sell a bit more in the next 10 minutes, so we wend our way and go back to them a bit later. We never put any pressure on anyone. We're just - whatever you want to give is fine, no worries if you haven't got anything this week.”

— Josie Cowgill, Trinity Rooms

There are 25 producers on the list of donors, and everyone I spoke to either lives or grows within a few miles of the market, and has been connected to the surplus system for some time.

In a small town with a regular market, relationships are long standing - and it’s no surprise that the surplus system itself sprang up from some of those that already existed between the Trinity Rooms and the market.

Josie Cowgill and Sarah Frazer had the idea to collect from the market to redistribute via the Trinity Rooms, back in 2020. During the lockdowns, like many people, Josie found herself with extra time to dedicate to supporting others in the community. And as a cook and events manager, her mind naturally turned to local food systems -and in particular food waste..

“We'd made contact through Gerb, who runs the market. He was supportive of us collecting the surplus food at the end of the market. Sarah Frazer went round the market first thing on Saturday morning to tell the market traders the plan. The first few weeks it was me with my husband and my stepdaughter doing the rounds and even though it was a new thing we came back with lots of produce.”

But as Josie says herself, the idea didn’t spring out of nowhere - it tapped into a wider flourishing of ideas around food and future building during the pandemic, that in turn had it’s roots in decades of community building.

Food Waste

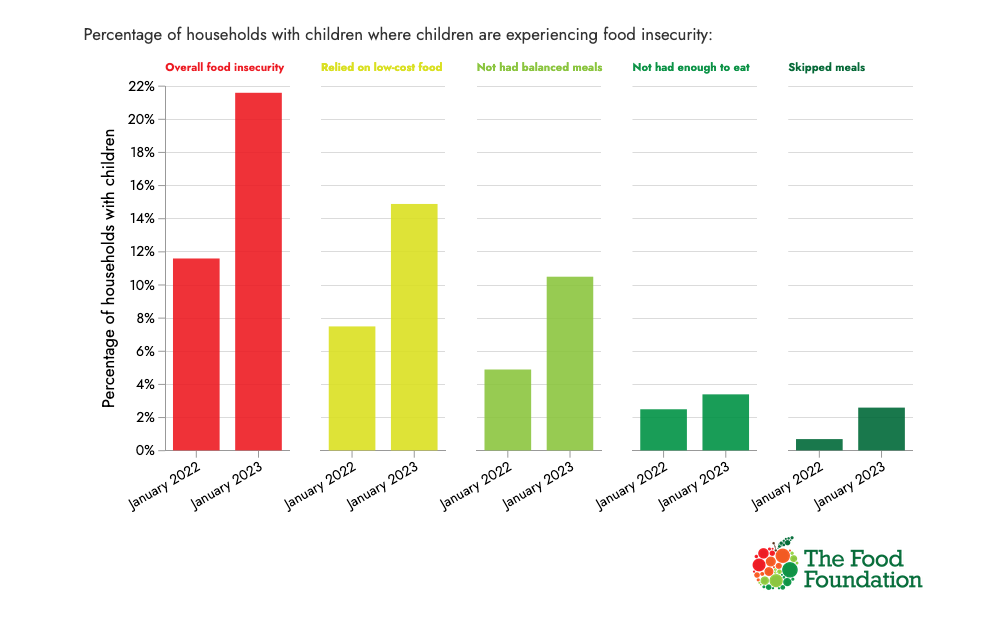

Food waste is not a new issue, nor is it a small one. Data published by the Food Foundation (March 2025) shows that in England, an estimated 7.3 million adults in 14 million households were affected by food insecurity this year, with children, single-parent families, those in receipt of Universal Credit or living with a disability much more likely to experience food insecurity.

With the poorest 10% spending a far larger proportion of their income on essentials such as food, the Joseph Rowntree Foundation and The Trussell Trust, a network of food banks around UK, state that current UC rates fall far short of covering the costs of basic needs, (nearly £140/month short, currently), and are in urgent need of reform.

It would be easy to assume that a food system based on trust and relationships - pay it forward, pay as you wish - can only operate in places that don’t face the most severe poverty. In the gentle English countryside, for example, now so beloved by west London emigres and Sunday times columnists.

In fact, the opposite is true. Hidden behind the cottagecore instagram reels and Country Living spreads, rural poverty is some of the most acute in the country and it is sky rocketing. Nationally, the picture is bleak.

Stroud itself, bohemian, picturesque and 90 minutes from London, has grappled hard with gentrification since the pandemic. With the second highest house price increase in the country this year, it was recently named the least affordable place to live in the UK, placing it squarely on the frontline of the rural housing crisis.

With inequality comes division, and food is the lightning rod for this, second only to housing itself.

Anyone unsure of the depth of feeling that surrounds what we eat - and where, and how, and why - would do well to look at the social media debate on a planned KFC in Stroud, which has rumbled on for some years now with the kind of anger normally reserved for serious crime.

On a larger scale, concerns over the sustainability of farming, and the livelihoods of those who work the land are always close to the surface.

Profound pressures on small scale producers, coupled with recent proposed changes to inheritance tax have tipped the farming community into direct action, with tractors blocking city streets, and country lanes now peppered with angry banners. Meanwhile, 15 years of cuts have reduced public service spending power by 40% in real terms since 2009, with local authorities all over the UK facing the spectre of insolvency.

Having so many families unable to reliably put food on the table, and so much going to waste at the other end of the social scale, has created an obvious and deepening injustice, and one that Stroud has been quietly resisting for decades.

Organisations like Marah have provided community led lunches and wide ranging support for over 20 years, and Stroud’s food bank opened its doors in 2011, both strongly supported by the community ever since.

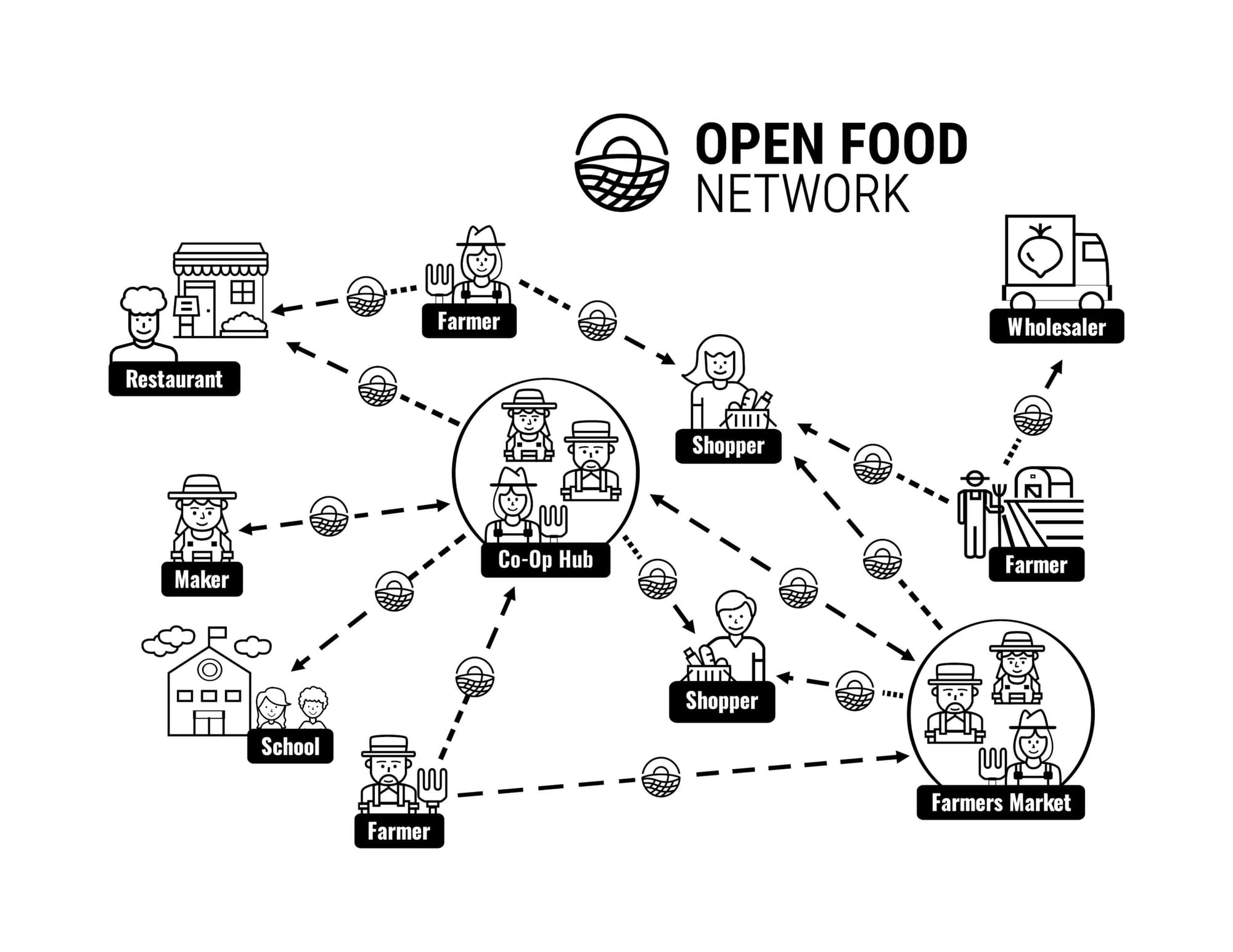

Always a home to innovation, Stroud’s much loved online grocery shop StroudCo was one of the first organisations in the UK to link local producers directly with local people ordering food online, and they went on to set up the Open Food Network. This aimed to reduce the footprint of food production, and crucially - to reduce food surplus at source, by circumnavigating large scale food retailers.

It’s a compelling idea that food waste and, on the flip side, food poverty, is entirely about individual responsibility, that it can be solved through better budgeting, or donating more at the end of the supermarket checkout.

In fact, as Jade Bashford of The Real Farming Trust points out, while it’s important to meet local need quickly, there is also a far larger issue that also must be tackled at the same time:

“Essentially, we shouldn’t be investing in a system that allows that surplus food to be created in the first place. Supermarkets used to have to pay to dispose of their waste, and now they can pass it on to food poverty groups on a large scale. Despite warehouses full of surplus, often those groups are still not getting the kind of food they actually need for families to thrive.

“Then there’s the waste that never even leaves the farm, because of the way they are contracted to supermarkets. For example, a farm might be told to deliver three tonnes of red cabbages, and they’ll be graded by colour, size, density and whether they fit in the packet and so on. And if they don’t meet the contract, the farmers are really in trouble.

“They’ve got no alternative to get their food to the market. So they are forced to grow a huge surplus of cabbages just to be sure of fulfilling the contract, much of which won’t ever get harvested because that costs money and they’re not getting paid for it. So the whole surplus food system is actually supporting supermarkets to behave like that, and the effect is, it’s trashing farming systems.”

— Jade Bashford

When the pandemic hit, the networks to resist scarcity in Stroud - both at a systemic and a local level - were already there to build on.

For many of those with extra time and secure income, the practical needs of lockdown connected them to their neighbours in a time of great challenge.

While the lockdowns have ended, the cost of living crisis has thrown that need into even sharper relief. Many of those early volunteers have remained, deepening their relationships locally, their numbers swelling with others keen to contribute, and a moment of community action has morphed into a movement.

At the same time as the food surplus movement began, and NoSH was emerging as a cooperative group of community food hubs, others were developing a Gloucestershire wide ‘gleaning’ network — the ancient practice of gathering leftover crops directly from fields now systematised into donations to food banks and community groups, ensuring that edible food doesn’t go to waste.

‘Feeding Gloucestershire’, part of Feeding Britain, was launched in 2021, focused on systemic change and building long term food security. The Long Table, with its pay as you can restaurants and ‘Freezers of Love’ arrived at a similar time, and has since become a much loved flagship organisation for inclusive, whole community solutions to poverty, demonstrating that food is not just food - it can be a site of radical thinking and imagining.

The Trinity Rooms was one of the first places to host a Freezer of Love, providing the Long Table’s home cooked meals for free, from the socially distanced porch of their building. You can still spot this practical, radical streak in their distinctive pantry sessions and cafe, and their efficient, large-scale approach to thinking about sharing food surplus.

A ‘pay it forward’ model also developed at the same time, allowing locals to join in and support the growing list of donating producers directly, by buying extra from them to be added to the ‘surplus’ stock.

It was typical of that time and of the spirit of Stroud that nobody waited for permission or funding to do the things that worked - they used their knowledge of what was really needed, and just cracked on with it.

Collecting Food

Back at the market, I pause at the Salt bakery stall. While we bag up pastries, dodging sugar hungry wasps, Pete the stall holder tells me that these artisanal baked goods would otherwise be fed to pigs. ‘I would rather food went to human beings’ he says.

There’s a strong sense of the interconnectedness of everything here - even the wasps get a quick defence for keeping down the fly population. As a local business, with a new bakery just about to open down the road, Pete said, it just made sense to them to donate extra goods to Stroud residents instead.

While most donate surplus, some, like the Golden Sheep Coffee company, have decided to donate the products they can still sell, simply out of a desire to give back to the people that support them. Most stall holders don’t see where their produce ends up, and do not meet the hundreds of people who benefit from it every week but being part of this project still feels like an obvious choice.

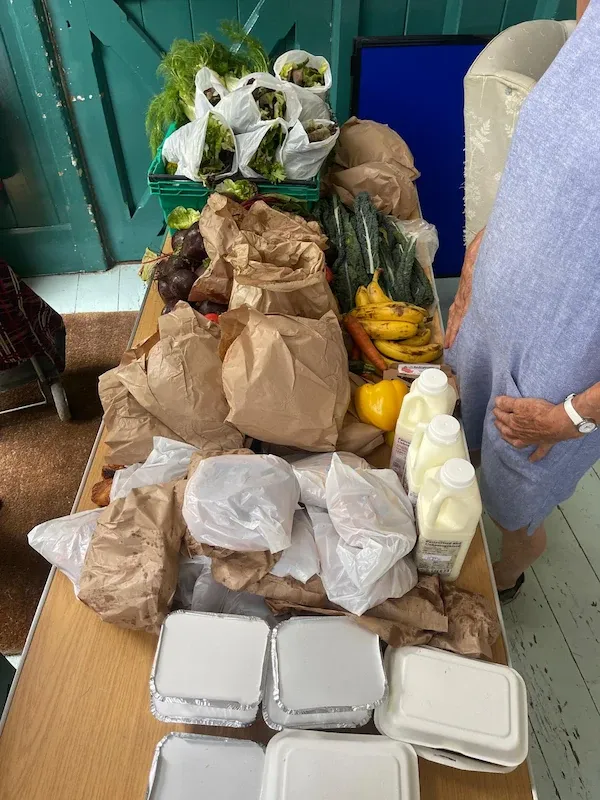

As we move between stalls, the trolley fills with a wide range of produce. It’s not just fruit and veg (although there is plenty of that) - soon we’re over-flowing with baked goods, cooked meats, plus milk and yoghurt from Jessie’s Ladies, a small local dairy farm.

Huge beetroots and sourdough loaves jostle for space with bags of locally roasted coffee and containers full of french street food, still warm from the stove. Half way through the collections we race the trolley back to the car to unload, wobbling over uneven cotswold stones, and I feel as though we’re robbing the kitchen of a very fancy restaurant.

After 45 minutes of pushing and loading in the heat, we’re all a lot sweatier than we were at the start, and Damaris’ car is full to bursting. We head up the hill to the Trinity Rooms, where we’re met by more volunteers.

Cheerful, warm and with the same swift practicality I’ve seen at the market, they immediately start unloading bags of food into the ‘Base Room’ at the back of the hall, a smaller space used by local groups and the food bank. The clock is ticking before the pantry opens to the public at 3pm, but before anything else happens, we weigh the food we’ve gathered.

— Josie Cowgill

Today we have had 117.36kg of food donated - roughly the weight of a large washing machine or (my preferred unit) the average giant panda!

I know that food waste is widespread and costly - but struggling to lay out these mounds of quality food, makes it feel real in a new way. It’s astonishing to know that it would otherwise be binned or, at best, composted.

Sorting the Food

So far the collection has been all about physical work. The next section is where the thinking begins: sorting what we have into sections, and allocating to different community groups according to the type of food, their storage capacity, and the particular needs of the residents.

It’s complicated, but it also happens smoothly and quickly, and much of that is down to Damaris. She is the only paid member of staff paid to support the food surplus programme - initially it was entirely volunteer led, but it soon became apparent that somebody needed to ‘hold’ the relationships and information required for efficiency.

Officially working 8 hours each week, but often volunteering more as required, Damaris’ passion for the work is obvious, but so too is the depth of her understanding of the needs of the groups she works with, which can change from week to week

Quickly, fresh food is shifted, rebagged and moved, myself and the other volunteers making sure anything still in storage from the previous week is moved to the front to be used first.

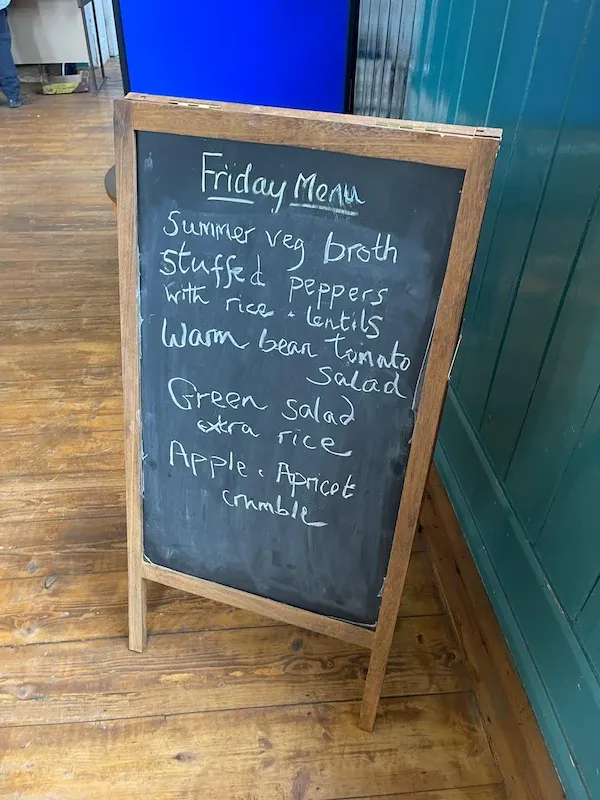

Some goes into the fridges at the Trinity Rooms for use at their highly popular Friday Community Cafe. More is put aside for a Monday pantry session in the same place, while some is stored for Rethink who host a weekly mental health cafe at the Trinity Rooms, cooking for around 20 people. Another community hub on nearby Chapel Street has food set aside for their lunchtime pantry on Wednesdays.

The Chapel Street community hub is part of a larger group of six hubs right across the town, all operating under the NOSH (Network of Stroud Hubs) banner. NOSH emerged first in the form of grassroots community groups, organising in the face of the pandemic and the cost of living crisis. While still independent, they have since collaborated under the NOSH umbrella, with support from Stroud Town Council - another by-product of that unprecedented moment for Stroud’s communities.

All of the hubs are volunteer led, and, again, it’s food that lies at the heart of how they support each other.

There’s an agility here in responding to need - as defined by the communities themselves - that is harder for commercial cafes with tiny margins. Volunteers are skilled in adapting whatever they’re given each week, turning sometimes unfamiliar ingredients into comforting meals that give more than just physical nourishment.

“A community kitchen is essential because it can take the things that won’t get used elsewhere. You know, those courgettes or scraggy beetroots that there’s a glut of and nobody wants, they can get chopped into spaghetti bolognese or put into cakes that everyone loves.

Community kitchens that can do that - and understand what their neighbours really want to eat - are absolutely fantastic. They've got potential to make a new market of producers who have got food to sell, that just doesn’t go anywhere else.”

— Jade Bashford

As the surplus system has evolved, the ties between the local council, residents and community organisations have become intricate and close - unusually so.

Anyone who has worked in frontline services elsewhere will know that ‘identities’ - volunteer or council staff, resident or community worker, donor or recipient - are often treated as clear cut and hierarchical, ignoring the fact that in reality, we might be many of those things at the same time.

Here, while safe boundaries and professional practices remain, there is an acknowledgement that no one part of someone’s identity sits in isolation from another. Ben Dayan who oversees the distribution of food to other NOSH hubs, also works with Good Small Farms, a donor stall at the market. Every council worker is also a resident, and they are often also a lunch guest or an event volunteer, a parent or a carer.

This deeper, ‘connecting the dots’ thinking runs through every aspect of Stroud’s approach to food and community.

“What needs to happen is people shouldn't be poor in the first place. When people are struggling long term, a bag of food is the least of their worries. Marginalisation is what you have to tackle - and that’s not about an empty cupboard, it’s the ten thousand issues that go with that: you're constantly stressed, you're juggling a budget that just isn’t enough, you can't pay for the school trip, you're worried about the rent, you've moved three times in the last three years, the freezer’s broken, and on an on.

“All of these things compound each other, and a bag of food doesn't touch it. So food banks and community kitchens exist are part of the picture, but it’s a mistake to think that the problem is solved just because they exist.”

— Jade Bashford

By 3pm, the first of the food surplus is ready to be redistributed directly to local residents. A table is set up in a doorway, and for half an hour a small stream of people arrive on bikes and on foot with baskets, waiting in the shade of the Trinity Rooms or under trees in its carefully tended ‘pocket park’, as the heat of the day reaches a crescendo.

Many people know each other, most are regulars. Conversations begin in the queue and are still going as we pack up to leave. Surprisingly for anyone who has ever worked around food poverty, there are no requirements to provide ID or referral forms, and there’s no line between volunteers and visitors - everyone takes something home.

“It’s of course about reducing landfill, reducing food waste, but it’s also about reducing food injustice and food inequality. What we really want is for there to be good quality food for everyone. The farmer's market food is healthy, local, fresh and seasonal - all the things that you want food to be. But the cost can be prohibitive. A lot of people can't afford to buy food at the market.”

‘With our pantries, anyone can turn up, we don't ask any questions. People can choose what they take. We don't restrict items but we might encourage people to remember that there are other people in the community who might also need the produce.’

— Josie Cowgill, Trinity Rooms

This might feel ‘fluffy’ - and it’s certainly true that the relationships feel easy and informal - but, a hard, practical expertise underpins this process.

A ‘pay as you wish’ system speaks to the way in which an effective food strategy is not actually about food, but about relationships. Making everyone feel like they are donating something every time is a big part of that:

“What the Trinity Rooms do well is creating ways to contribute. They can say to me, when I turn up with yet another crate of spinach - that’s perfect, thank you! I need to go to lunch sometimes because I’m working by myself. So I’m going there to meet a need, but I take my spinach so I don't feel like a needy person, i feel like I’m part of something. The market collection is also a really good volunteer role for people, because it’s on a Saturday afternoon, you can just drop in in for an hour or two and it's friendly.

“You know, people need to contribute, they need to love as well as to be loved. That’s important. It’s a lot of work, but the Trinity Rooms make it look easy. You’d never know how much labour goes into making everyone feel valued. It just feels like a well oiled machine, like an informal and happy place. It’s really important that, it's actually sometimes more important than the food itself.”

“I’ve got a lot of time for the hubs and what they’re trying to do - the Trinity Rooms in particular, it’s a reflection of the professionalism of the people involved, they’ve come from careers where they’re able to really think about organisation and structure.”

— Eric Walters, Good Small Farms

This level of planning, structure and care is not just a nice to have - it is an essential part of success in tackling poverty. And yet, that’s exactly what is hardest to achieve when resources are limited - giving us the catch 22 of scarcity, from households to charities to national governments.

As the state recedes, it’s individuals and small groups that have stepped in, providing a patchwork of support to fill the gaping holes in the safety net. This is deeply necessary work, and - for precisely this reason - deeply undervalued.

Without the security of long term funding and economies of scale, many grassroots organisations are forced to reinvent the wheel over and over again as people and expertise come and go.

So much of the work communities do to take care of each other has scarcity baked into it, designed to scrabble to meet an exponential curve of need, instead of preventing it. Not so here.

It’s no coincidence that alongside receiving surplus donations from local growers, the Trinity Rooms hosts regular meetings, to discuss long term food resilience against the backdrop of climate crisis and political activism. While it connects all of the pantries and hubs in the area with a secure stream of high quality food, the surplus system also, crucially, connects people through time, as well as across communities.

It is the depth and scale of planning for the future that marks out Stroud’s food culture.

“[the surplus food system] is only the beginning - it’s one thing to have this connectivity but then there’s looking at what do we do with the surplus to secure us in the future - can we process it, can we preserve it - the Trinity Rooms are at the forefront of that, renting their kitchen out so food can be turned into soups and preserves, to see us through when the harvest stops.

“For me, farming is a long term thing, we’re investing in the quality of the soil, so we’re thinking in 10 year terms. When people are thinking about immediate supply - the people who need food now, sometimes it can be just about feeding people anything. But the majority of farmers have 20 and 30 year horizons, they’re thinking about the quality of food, the quality of soil and the quality of wildlife. This is how you think about solving tomorrow’s food problems.”

— Eric Walters

Surplus this may be, but these are not crumbs from the table. In my time in support work, I have seen many food collections for community kitchens, and never before have they included Greggs steak bakes and pheasant eggs and venison.

Food is such a personal thing, I wondered if everyone in the community was always happy with bougie farmer’s market fare. But the pheasant eggs are a good example of the journey this process has taken everyone on.

“Protein is often the most expensive part of food. So to be given free protein; eggs, meat or dairy, is an absolute bonus. There’s no market for pheasant eggs, they just get incinerated. So we are happy to make use of them - they taste the same as hen’s eggs, you just use double the number. Our cooks and volunteers created many delicious meals and cakes with them at our community cafe”

— Josie Cowgill

There’s a seditious feel to such a high end haul being given out across the town, and about the care with which familiar, accessible meals are mingled with the artisanal. The community cafes use high quality ingredients - but a lot of thought goes into serving them up each week as familiar, nourishing meals. There’s an understanding here that comfort and a sense of control are closely linked, and for anything to change, we need both.

Luxury Thinking

Stroud’s surplus system is simple, cost effective and - astonishingly for a country beset by food poverty - not mainstream in the UK.

There are other places working to similar principles, but many of those are in urban centres such as London, Birmingham and Brighton - and there are few rural collectives working in such an ambitious way.

When confronted with a literal and metaphorical empty larder, the people of Stroud didn’t settle for the thin gruel of charity. Instead, they snapped their fingers and produced a feast for the whole town.

To those who have worked on the front line of service provision over the last half decade, this does indeed feel fantastical - like the pots of gold in fairy tales, where the more we give away, the more we have.

There is no single magician. This is the imagination of hundreds of people at work, plus a few determined and skilled individuals with their hands on the tiller.

Crucial to its success is that the language of ‘need’ and ‘lack’ have vanished.

Instead of just describing scarcity, a surplus system goes looking for plenty, and finds it - in its people, its skills and - most decadent of all - in planning for the future. This is not a straight logistical line taking food from A to B - this is a tangled web of care - for the land, for our neighbours, for the next generation.

And like all good ideas, it’s an obvious one. As a solution to food inequality, it feels almost embarrassingly cheap and simple - just take our extra food and share it with everyone, no questions asked.

For anyone reading this and wondering why you can’t have the same system where you live, I’d say - you can. All the ingredients are there. Growers who care about the land, people who care about their neighbours, extra food going to waste, people who need a good meal and good company, just a few people with time and resources to spare.

I guarantee these exist in every community in the UK. We don’t need permission, the secret ingredient is only imagining that it’s possible to do things differently. We have enough money, we have enough houses, we have enough food. All we have to do is be brave enough to pull up a chair and tuck in.

Emma Kernahan, otherwise known as @crappyliving on instagram, is co-Director of Dialect Writers, and this autumn is touring the south west as one third of the mythical parish council, Lost Mythos (@lost.mythos)

Amplify Stroud is supported by Dialect rural writers collective. Dialect offers mentorship, encouragement and self-study courses as well as publishing.

You can find out more at https://www.dialect.org.uk/

Member discussion