Common Ground

Nikki Owen | Dialect

October 2025

I woke up in my campervan. A storm had passed. The previous night, the heavens had opened, rain raging, wind roaring, chaos everywhere. The sea was angry, the crows were livid, nature was up in arms. And then morning came. Quiet. Soft. The sun rose, gentle and whispering, crawling through the debris of the night to reach the daybreak.

I made a coffee. Things felt at peace. Loving a morning, I slid open the doors of my camper and, steam rising from the mug in my hands, I blinked through the sunlight dancing in the trees, feeling, in that moment, at one with the world.

Until I saw it. There, attached to a pole on a caravan, flapping in the cool breeze like a sharp slap: an England flag.

In this first piece in a new series for Amplify Stroud called Common Ground I explore nationalism, the belief that a nation’s interests and identity come before others.

I was going to talk about the gender pay gap, and I will, equality and equity requiring more focus, more concerted effort and intention than it currently receives. But recent country-wide events have turned the thought-ship to more urgent waters.

Waters is the operative word. I’m Irish. Born in Dublin, Irish passport, in the early 1980s, my family came over to Britain on a boat. We were economic migrants. My dad needed a job, and the family needed to make a living, and so we moved into a council estate and set up home.

It was the time of the IRA, and there were bombings in Ireland and on the UK mainland, and what we faced when we arrived in Britain as kids was, basically, abuse. We were called Paddies daily. Terrorists, too, was another word used. And every day we were told to go back to where we came from. I was five.

But I am lucky. I’m a white woman. I didn’t come over on a small boat from Syria, for example. I sound British now, a tad Northern, aye up, when I have a cuppa or chat to my brother, changed my accent long ago to instinctively fit in.

And then I saw that England flag.

What must it be like? When my eyes landed on the flag, that’s the phrase that walked into my head, opened a door and has not left since. What must it be like? What must it be like to be an immigrant to the UK and not be white?

What must it be like to be British-born and not be white? What must it be like for someone white and UK-born who can’t find a job or pay for food? What must it be like?

I wanted to delve into that concept, write an opinion piece about belonging, something reflective, structured. But then I stumbled, and thought, hang on - I’m a creative writer, and we show rather than tell. So what if we show what it must be like?

And so this piece changed.

It became Common Ground, a new series for Amplify Stroud exploring belonging, identity and division through real stories told in the first person, from both sides of the divide, from behind the headlines.

It’s an attempt, of sorts, to try to walk in another’s shoes, create, if possible, empathy. Psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen says that empathy is the glue that holds society together, that when we check in on each other and ensure no one is left out, we are less likely to harm, bully - or dehumanise.

What you are about to read are two interviews: one from a woman who came to Britain as a child more than sixty years ago, and one from a white man who flies the England flag.

It was powerful to listen to their stories as I sat with them, and I think it’s powerful to leave them here with you now to read. To find the common ground.

The Immigrant

“I have been in this country for over sixty years. I came here as a child with my mother to join my father, who had already arrived. We started in Reading, where my father worked in a factory.

Even then, he faced abuse. But there were also kindnesses. Our neighbours on one side were from Africa, a lovely family. On the other side were working-class English people who were warm and generous. They passed on toys their son had grown out of, and when my father was given a turkey at Christmas, we gave it to our neighbours because we didn’t eat turkey. It felt like a community. But outside that one street, there was racism.

As a child, I grew up with fear — fear of being attacked, fear of being called names. When we moved to Luton, it became worse. Children would run out of their houses to shout abuse. My eldest brother’s jacket was set on fire by thugs. My father was nearly run over by a neighbour. We had to move houses.

Later, when my brother drove a taxi, some men refused to pay him. They beat him, broke his glasses, so he couldn’t see to drive. There has always been that fear, and those memories are coming back now because of the rise of the Far Right.

I hear people say, “Go back home.” But this is my home. I have lived here all my life. I don’t have another place to go. Yes, my roots are in Kashmir, but I have never lived there and I have never been back. I built my life here. My children were born and raised here. I have friends, community, work I love. Belonging, for me, means being accepted as part of something.

I live on this street. I may not know everyone, but I feel part of it. That matters. But when I see flags flying — not for football, not for celebration, but as a statement of exclusion — it makes the hairs on my neck stand up. It is not an imagined fear. I have lived what racism feels like: physical, verbal, systemic.

What I would say to those who want people like me gone is: why? What is it about me you don’t like? Is it my skin colour? The way I dress? The food I eat?

Because otherwise, people like me are contributing. I went through the British education system. I went to university. I have always worked. I’ve paid taxes all my life. I smile at strangers. I say hello. All are welcome.

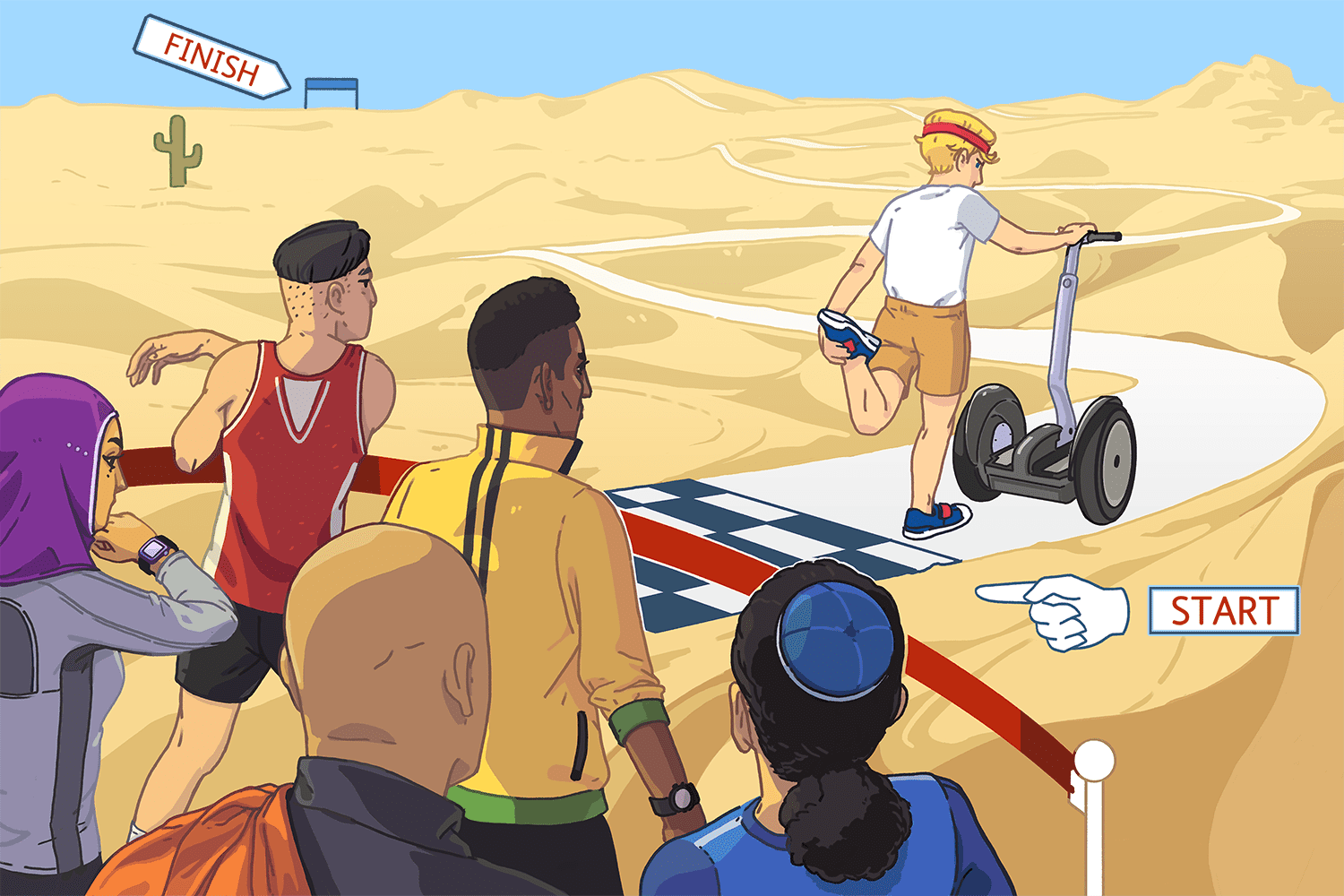

The problem is not immigrants. The problem is government. I heard a woman on the radio say she wanted all people of colour to go back because her disabled son wasn’t getting support. My heart broke. Her problem is real, but the cause isn’t people like me. It is government not providing what it should. Asylum seekers are not given luxury — they live on about ten pounds a week. Yet the Far Right say they are given phones and money. It is not true.

People talk about boats. Well, what about those who own yachts and sail freely on the seas? Nobody touches them. Why are the wealthy not being taxed? The world has enough money and food for everybody to live comfortably, but there is no sharing because one percent owns so much. If they were taxed properly, the NHS could be supported, public transport could be supported, everyone with disabled children could be supported. That would help one hundred per cent — white, Black, Asian.

Do people understand what white privilege is — that just by having the colour of your skin as white, throughout history, there have been layers and layers of privilege?

Just because you’re white, somehow you’re put above other people, and everybody else is below you.

That is wrong. That creates division. I know this because I’ve lived it. We are affected. We are so affected. And yet if you are a white person, you just go on through.

We hold British passports, and we are here legally, we do everything by the book. We are just normal British citizens. But by the mere thing of having skin of a different colour, we are not granted those privileges.

Just the mere sort of thing of being born — once you’re born, all this stuff starts to pile on to you. But if we could just take all that away, strip it off, what would be left? It is a oneness with humanity. Can we not have a oneness with humanity? Wouldn’t the world be much, much better? That is the world I want to manifest.

People need to sit down and talk, share their struggles, and realise they are often the same. White children are bullied at school. Asian children are bullied at school. The pain is the same. If we spoke to each other, we would find common ground.

Religion is religion is religion. Most religions say the same thing: love. We should celebrate difference, not fear it.

I want to be seen for who I am. I believe in hope. I believe we can choose compassion.

Just the other day, I helped a woman in a supermarket car park when her trolley overturned. I didn’t think about what colour her skin was. She needed help, so I helped. That’s what being human is.”

The English Flag Bearer

“I grew up in care after my parents split up when I was seven. I was nine when I went into foster care. I was there for about ten months, then I went to live with my dad. Things were messy. My mum and dad didn’t get on, and I was stuck in the middle. I wanted the best of both worlds, to see them both. When I chose to live with my mum, my dad cut me off.

At the ages of twelve and thirteen, I started trying new things. Smoking weed, then cigarettes, then I tried drinking. With the drink, I felt I had more courage, and it made all the things that used to be on my mind go away. Before I knew it, I was actually experiencing withdrawals at school. I was an alcoholic at fifteen.

After that, I worked here and there — warehouses, call centres. I ran a team, and I worked for the ambulance service, all whilst being a functioning alcoholic. My relationships broke down. I tried killing myself.

I lost jobs, flats, friends. I ended up having 32 inpatient detoxes. I began to have oesophagal varices and they were bursting. On three of those seven bleeds, I actually died, my heartbeat stopped, and I was defibrillated. My family were told I wouldn’t leave hospital, but I did.

I was homeless again, living in a tent. I begged for help and got nowhere. I knew the only thing that was going to save me — the only way I could get a roof over my head that would separate me from alcohol — would be prison. I manufactured myself into prison. I smashed a window, waited for the police, asked to be remanded. They thought I was mad, but I needed to get into the system.

In prison, something happened I can’t explain. I went in an atheist and came out a believer. I had a very supernatural experience. I became a follower of Christ.

I came out and started again. I met my partner. I’m a dad now.

One day, the eldest said, “You know you’re with my mum — does that mean you’re now my dad and I can call you Dad?” I said, “You can call me whatever you want, as long as it’s not a swear word.” He ran to his friends and said, “I’ve got a dad.”

That changed me.

I’ve got health problems now from the years of drinking — cirrhosis, blood issues, trouble with my legs — I’m in and out of hospital. I’ve worked with probation, I’ve spoken to young offenders, I’ve done workshops talking about my life, what I went through, and I signpost people to the right help I didn’t get.

I believe the family unit is nuclear — having both parents together gives a child balance. The separation I experienced really affected me and my behaviour. Most people in prison, a lot of them, grew up without a father or in a broken home.

Belonging… I don’t know, it’s hard. You could belong to one thing one minute and belong to a different thing the next. In a community sense — where I live — I belong to the community that I live in. It’s my home, where I live with my residents.

I’m proud to be English. It’s in my DNA — my heritage — my football team, my rugby team, it’s my home, it’s who I would fight for if I had to. But that doesn’t mean shutting people out.

A 2018 BBC article exploring Englishness and identity

A racist is someone who targets an individual or doesn’t believe an individual has the same rights as them, or they see themselves as superior because of the colour of their skin or where they come from.

Those old groups — the white ethno-nationalists — they were genuine racists. I don’t agree with that.

“Go back to where you came from” — that’s disgusting. It’s vile. I watched a man say it to a young girl, and it turned my stomach.

I’ve got black British friends. I’ve got British Muslim friends who are proud of Britain — they love this country. Some of them even get abuse from their own communities because of that, which is wrong.

That flag represents you as much as it represents me, if you love Britain.

We should be able to be British and gay, British and Muslim, British and Sikh, British and Hindu — just be British.

I used to be angry with the world. Now I try to understand it. I want more unity, more discussion, more debate.

We are not enemies. I’d like to see a venue where you have someone from one side and someone from the other, to sit and talk. That would start repairing divisions — that’s how you start to understand, that’s how you heal.

People are worried and scared, you know — about housing, jobs, safety — and when you’ve begged for help and been ignored, it shapes how you view everything. I don’t want shouting or blaming.

I want people to be able to talk about their fears without being called names and to listen when others talk about theirs. We’ve all got stories.

I’ve done things I regret, but I’ve also survived things I shouldn’t have. I’m not proud of everything I’ve done, but I’m proud I didn’t give up. I’m alive. I’ve got love. That is everything.”

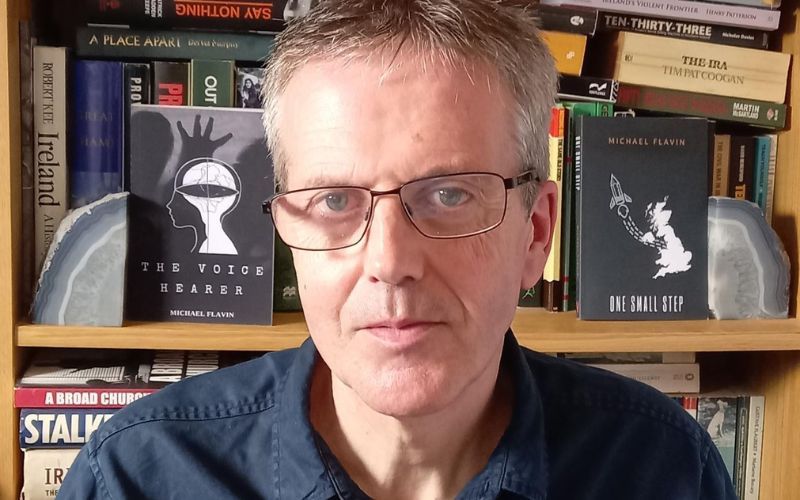

Nikki Owen is a multi-award-winning author, book coach and creative-writing lecturer.

She is co-founder of This Ends Now, a non-profit working towards a world free from gender-based oppression, and a mentor for Dialect Writers. Her work explores empathy, belonging and the stories that connect us.

If you have been affected by anything in this article, or if you’re feeling isolated or unsafe, here are some people and groups that can help:

SARI (Stand Against Racism & Inequality)

0117 942 0060 | saricharity.org.uk

Stroud Against Racism (SAR) — community-led action and support facebook.com/stroudagainstracism

This Ends Now — local campaign for gender equality and inclusion thisendsnow.co.uk

Gloucestershire Action for Refugees and Asylum Seekers (GARAS)

01452 550528 | garas.org.uk

Gloucestershire Domestic Abuse Support Service (GDASS)

01452 726570 | gdass.org.uk

Mind Gloucestershire

0300 123 3393 | mind.org.uk

Crimestoppers (anonymous hate-crime reporting)

0800 555 111 | crimestoppers-uk.org

Amplify Stroud is supported by Dialect rural writers collective. Dialect offers mentorship, encouragement and self-study courses as well as publishing.

You can find out more at https://www.dialect.org.uk/

Member discussion