“Paradoxes of Danger” — the Cass Review and its implications for trans youth

by Eli Parry

ONE MONTH ON, THE PUBLICATION OF the Cass Review on gender identity services has had a myriad of reactions from scholarly literature, media articles, political statements, and has erupted through social media.

It is clear to many now that there is a spiderweb of incongruence within the Cass Review: most namely the absence of definitive conclusions on the real effects of hormone therapy, and the analytically illogical weight that this had on the recommendation to restrict access to therapeutic interventions.

Cass’ own anti-trans inclinations and the political environment in the UK could explain this oblique in data and analysis —

If this report is a epistemological leap — a fallacy in medicine — one where a plethora of research pre-exists its inception, then it leaves few alternatives to imagine why such a report would be published.

Commissioned by NHS England, Hilary Cass oversaw a review which would investigate provisions for transgender healthcare after the Care Quality Commission found that the Tavistock Gender Identity Development Service was “inadequate” in January 2021.

In conjunction with anti-trans sentiments in social opinion, conflict in political spheres, and judicial pressure on transgender medical care after the Bell Vs Tavistock case, there has been a cumulation of events that have peaked the lobby for a NHS mandated review into the question of autonomy for trans youth over their health and identities.

Using healthcare services — that are already falling into the seemingly unsalvageable depths of financialisation due to austerity and the privatisation of public services — as a tool for gaining political capital adds to the perversity.

This review’s purpose was not only to implement changes in transgender care for young people, but was a vehicle for championing the legitimacy of oppressive rhetorics and policies.

Yet this all makes some sort of wretched sense when considering the political aims of the current ruling party.

It is hard to name the ideological underpinning of Sunak’s government, but it’s certain that it is one of intolerance utilised to re-affirm division through misinformation.

During election year, distraction tactics, scapegoating, and the exploitation of wider global issues function to scramble for a disparaging electorate.

A population that is simultaneously torpid and infuriated due to the government's flaccid attempts to resurrect the economy, purposeful lackadaisicalness over mounting social issues, and relentless profit-driven warmongering.

The Tories have throughout their current period of office been commenting on the illegitimacy of trans identities.

They have magnified in on neoliberal conceptualisations on rights, or the restrictions of them, hailing in the imperialism imposed gender binary and norms to expand the advancement of discriminatory political agendas.

Labour is not innocent of this either — being reactionary to the report and retreating away from past pledges for trans rights as a means for furthering their interests in the next general election.

Now, the Cass Review has provided an “evidenced”, “rational”, coup de force onto the struggles that trans people face, specifically now trans youth.

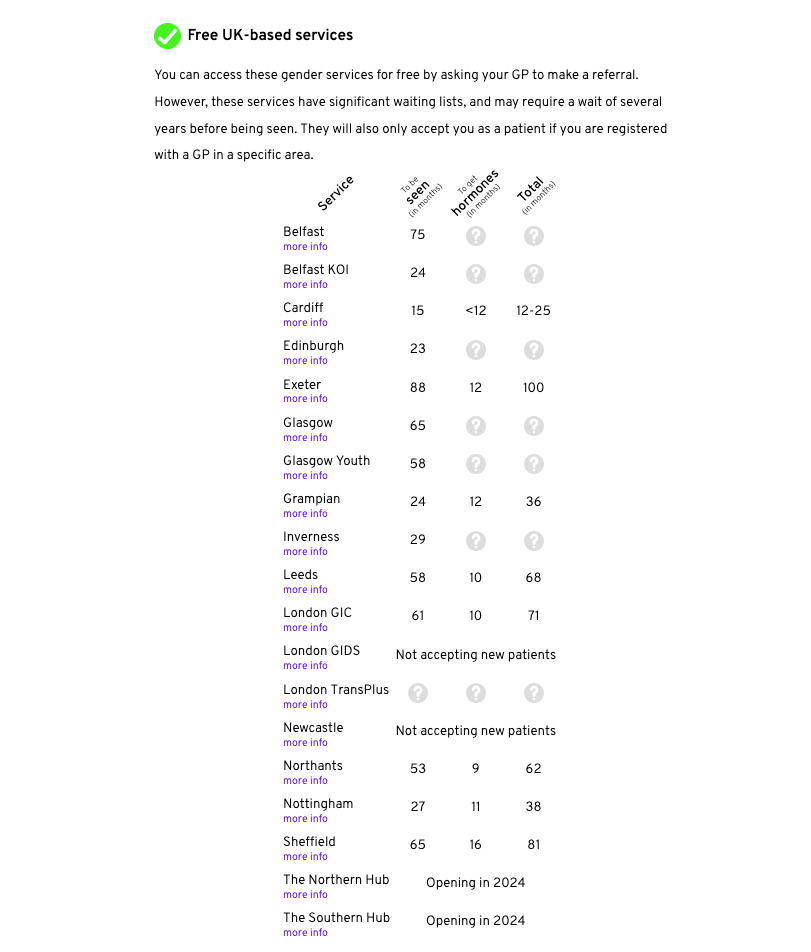

Being a young trans person was already a prescription for enduring violent suppression, especially with access to gender care being outstandingly poor (in part due to waiting times, as well as precarious and bureaucratic referral systems) and a mental health system that is on the brink of, if not effectively in, debilitation.

Consequential restrictions on what is part of an already limited healthcare system for trans youth is now feeding narratives that further discrimination

Gender diversity & mental health

THERE HAS BEEN A DISTINCT FOCUS IN Cass’ reporting that identifies the intersection between gender diverse youth, their dysphoria and the mental health epidemic.

The analysis infers that transgender identities present as a mental health issue and does not consider that the inverse could exist as having the dominant role in this dialectic: lived experiences of inequality and restrictions on transitioning may well be a driving force of poor mental health in young trans folk.

Hormone treatments are capable of delaying puberty reversibly, and the use of such treatments have been shown to improve mental health and social lives, as well as decrease suicidal feelings.

Pessimistically, its likely that the answer will be “no”.

The overt portrayal of gender affirming care as an “over medicalisalised” mental health issue shows an open disregard for the impact of this broken system — one that has a wider disparity in provisions for equality and access to health care services, an issue that will disproportionately impact trans youth throughout their lifetimes.

Comprehensive studies have indicated that the expansion of research into the benefits of early treatment for youth will, in eventuality, improve access for health care.

However, Cass recommends greater pharmaceutical interventions for young people struggling with psychological distress, whilst removing specialist healthcare for gender: a medicalisation paradox that only exposes Cass’ own transphobic bias.

It is not that being trans is a mental illness, it is that the arms of the state are so inefficient in their roles to deliver care, and social life has been so wrought towards hatred, that the medicalisation of this ontology, fomented by inequality, as a mental illness seems largely inevitable.

These are alarming misrepresentations to play off in what has come to be a highly renowned “official” take on gender affirming care.

Escalating concerns regarding the review arise as Cass infers that trans-ness has a causal relationship with sociality, specifically peer-to-peer contagion, as if identity can be an infectious disease, fearfully provoking us to wonder how political agents will attempt decontamination.

Discourse disavowing identity sovereignty and promoting anti-queer tropes pre-exist the report. Individual gayness has long been labelled as an “illness”, and queer communities as a societal malaise engendered by the hysterical fear of the spread of the “gay agenda”.

The demonisation and stigmatisation of trans youth as dangerous identities, pathologised in order to be to be “cured”, is also echoed in language used in conversion therapy spaces.

Hence, the utilisation of disease epidemiology in contexts of rights around gender dysphoria is unsurprising and founded in repressive cultural histories.

Now, debating gender care is being used as a vehicle towards not only impeding transitioning but the right to be considered as unreservedly human. Governmental bodies and the media have begun to lean into playing with dehumanising stereotypes that have historically been mechanised by oppressive forms of politics to enact violence upon populations who are made vulnerable by power structures.

The perceived threat of trans folk has only made life for trans youth more dangerous rather than securing the lives of those outside the queer community.

Social Transitioning

THE RETICENCE AROUND TRANSITIONING IN THE review is equally expressed through the delegitimisation of social transitioning.

Cass refuses to sufficiently evidence exhaustive conclusions around social transitioning as a process which can be affirming for young people’s identities, and instead recommends caution around it.

This represents the paradoxical ideologue of Cass’ fear around the proposed irreversible harms of transitioning as — not withstanding the reversible effects of some hormone therapies for gender affirming care — social transitioning is decisively changeable and can help young people in their resolve around their identities before medical intervention.

The result mimics well renowned limits on expressions of creativity and academic critical thinking for young people.

Interventions in schools such as surveillance over young people’s bodies, dangerous practices against trans youth and the proposed removal of teaching gender identity, have been strategically sanctioned to preserve gender norms in the name of protecting said children, but only cis-kids.

This is a reverberation of the removal of queer identities from public visibility by other policies in our recent political memory, such as Thatcher’s Section 28 which also aimed to entrench gender norms and misrepresent queerness as a danger to society.

In attempting to use fearfulness and protectiveness over the wellbeing of children as part of the anti-trans propaganda, trans people are continually demonised.

#OtD 24 May 1988 the homophobic 'Section 28' passed into law in the UK. It stated that local authorities must not "promote homosexuality" or "the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship." The law sparked a wave of resistance. https://t.co/7CCNFuBQBr pic.twitter.com/bbJEoqEQ74

— Working Class History (@wrkclasshistory) May 24, 2024

This annihilation of personhood delegitimises individual autonomy and reinforces anti-queer attitudes, and by extension, policies that put trans people in a perpetual state of insecurity.

In parallel to this, the pivotal role of women’s safety in the argument over the use of bathrooms reminds us of the trope “I don’t mind you doing what you want so long as its not in my face” that popularised when homosexual relationships began to appear in TV and film.

Increasing negative visibility for trans folk in the media is likely a compounding factor that is reaching beyond the perception that trans folk are dangerously invading private space.

They have now been politically mechanised to be a threat in public too — they’ll infect your kids with their trans-ness — validating perilous narratives that target trans folk. An atmospheric violence, the permeations of which can be traced historically, is providing the conditions for the victimisation of trans folk.

“Witch-hunting in all its different forms is also a powerful means to destroy communal relations, injecting the suspicion that underneath the neighbour, the friend, the lover hides another person, lusting for power, sex, wealth, or simply wanting to commit evil deeds.”

― Silvia Federici, Witches, Witch-Hunting, and Women

Transness as an Identity

TRANS-NESS AS AN IDENTITY, COMMUNITY, AND symbol, has increasingly become a politically charged topic, one which is inseparable from relations of power. Folk of the global majority and refugees experience greater repression, violence and mental health issues, and being trans in addition, will intensify such discrimination.

Likewise, the intersectionality of trans-misogyny must be considered whereby fem-identifying individuals are more likely to experience violence, as murder rates increase with these crossings of identities.

Passing has become a central facet to survival as a trans person, functioning as a provision for protection as not to raise attention — symbolic of the colonially enforced norms on gender expression.

Ignorance to the impact of these power relationships and white cis-normative supremacy does a disservice to authentically represent the needs of trans folk across the UK. In excluding the differential experiences of trans youth Cass is perpetuating imperialistic inclinations to erase the lives and struggles of people of global majority heritage.

Consequentially, the review provides an exposé on political agendas and a wider nexus of oppressive power structures that breed inequality. It is impossible to consider the trans struggle in isolation under this system of supremacy.

Just as Islamophobia — frequently expressed in the UK as a racist anti-migration sentiment — has been mechanised to implement divisive cruelty, anti-trans doctrine has become a site of safety due to the tactical use of the “trans debate” politically.

There are similarities in the proposed, or perceived, threats that Muslims and trans folk pose: as if they’re putting women and children at risk, or they’re infringing on our cultural hegemony.

Political agents are too transparent however, their doubling down on colonial norms to maintain power are visible, and vapid in their admissibility. Trans-ness derails the imperialist agenda and so is a threat to a state that seeks to maintain this oppressive normalcy.

As a community that acts to subvert and resist toxic gender norms and ways of relating, trans youth are being exploited by political powers for their own broader destructive ends: delineating an alienated population in order to retain and administer control.

"today the colour line is the poverty line is the power line ... that is why you cannot fight racism without also fighting imperialism. You cannot fight for the cause of black people without fighting for the cause of working people. You cannot, in the final analysis, fight oppression without at the same time fighting exploitation"

— A. Sivanandan, Communities of Resistance

The politics of gender diversity

THERE IS NOTHING TO SEPARATE THIS review from politics, and as such, politics cannot be separated from youth access to services.

It speaks to an entrenched political playground whereby older people make decisions on behalf of youth, and cis-people consistently make judgements over trans folk.

Resolving the ambiguous language around harm is imperative to provide actual, reasonable and evidenced, advice to healthcare services.

Equally, resilience must be fostered to act against ideological fantasies that promote trans-ness as an illness, so that transitioning can become an enabling factor for increasing mental wellbeing, The Cass Review is a methodological aporia, and whilst the effect on gender care access is a paramount issue, it is the anti-trans sentiment that too requires interrogation and action on, lest the restriction or revision of trans rights continue.

More studies to re-legitimise gender affirming care alone may do little to ignite the fire that brings down the repression of communities and restrictions on self-sovereignty.

It is undoubtable that the effects of this review will be felt by trans youth across the international community, not only in relation to their access to healthcare.

Although it may not be directly visible, rising tensions and restrictions in society are connected to one another, and the Cass Review will now be implicated too. The methods of control inflicted on populations by Western-imperial conventions on identity politics (that exclude trans people and other disempowered people from communal societies, monetary accumulation and work, healthcare, education and housing) all culminate in increased harassment, discrimination and suffering worldwide.

The embroiled nature of these issues tells us that when it comes to the forces of power, our experiences are intrinsic to each other, the context that allowed for and produced the Cass Review is one that affects us all.

In disentangling stale neoliberal promises of the social contract, equality and freedoms, trans erasure can be recovered from by disobeying the state that forces us into this stagnant oppression.

In breaking down this unjustness, systems of care can be rebuilt to support the needs of those made most vulnerable. Individualistic targeted attacks on liberties and trans personhood denies community solidarity by working off the back of decades of attempts to distort and destroy queerness.

A reclamation of lost transgender radical histories and forming solidarity between feminist and queer revolutionary movements will enable a resurrection from forced collective organisational amnesia, empowering justice and joy for trans folk.

As colonial control functions through the global capitalist system of hierarchical subordination, we must push to celebrate internationalist trans solidarity with other struggles to learn from each other’s wins and take back sovereignty together.

The imperial foisting of gender norms that bolsters such control must therefore be examined and breached. As Micah Bazant succinctly put it: “No pride for some of us without liberation for all of us.” In collective dissent and persistence, trans folk will be able to form their own utopia.

“We have to remain visible. They have to see us, they have to know that we're not going [nowhere]… and they have to get over it. I don't need their permission to exist; I exist in spite of them... we have a culture, we have a history, we have a reason to be here. We have a purpose. We're entitled to be loved, and seek happiness, and share that with the people that we care about.”

— Miss Major Griffin-Gracey

A paradox of danger

TRANS FOLK EXIST IN a paradox of danger in contemporary UK society. They are perceived as a contagious blight, a revolutionary threat, and are at risk from narratives which promote violences that limit freedoms and personhood.

Cass has done little apart from amplifying bifurcation around this issue — of what is really human rights — further in line with the interests of the current government, using the victimisation of trans youth to deepen constraints.

The needs of trans youth are not being met, and at this present moment perhaps their greatest need is to be treated as humans with agency, rather than objects for the expansion of state apparatus and political power.

Eli Parry is a youth worker, activist and amateur writer from Stroud. Having graduated university in Anthropology, they are interested in writing about social issues, radical politics, culture and critical thought.

Member discussion