The racist Clock and the Right’s Culture War, Stroud need not be divided

By Jamie O’Dell

Bright red lips, tobacco leaf skirt, club in hand whilst tethered to a wall by its neck. It’s hard to miss the racist and infantilizing depiction of Black people, that has defined their treatment and disposition throughout the colonial era, that makes up the Black Boy Clock in Stroud.

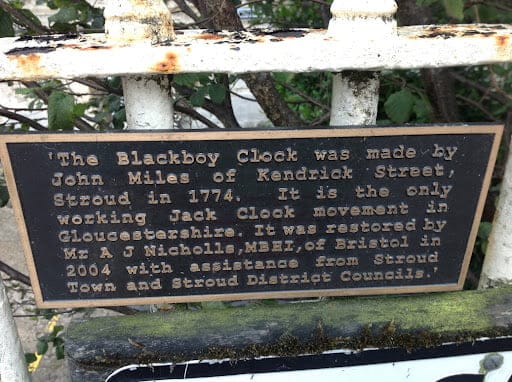

Constructed in 1774, during the height of the trans atlantic slave trade, the Clock has been placed on the Grade II listed building at the top of Stroud town since 1844. Throughout this time, it has overlooked the Black people who lived in Stroud since the clock’s construction, providing a vivid and well maintained example of how Britain, and by extension Stroud, has viewed and marginalised Black people for centuries.

The impact of the Clock’s presence has been demonstrated in the testimonies of Black and other racialised people. Quoted in the Stroud News and Journal (SNJ), Dan Guthrie, who walked past the statue every day on his way to school and believes the statue should be moved to a museum, explained the impact the Clock had upon him.

“As a person of colour, walking past it all this time has made me feel incredibly uncomfortable in the place that I call home; a bygone relic of the transatlantic slave trade looking down at me and reminding me of the way that Black bodies were treated in that period of time.”

Another person of colour interviewed for this article, who also wants the Clock moved to a museum, stated that: “To have an enslaved child ‘golly’ lookalike up in pride of place is not healthy, respectful or decent. The BlackBoy Clock normalises the degrading of Black people and shows no respect for the hurt and harm of this, nor the history it insultingly glosses over.”

Despite being such a stark example of racism, however, the reaction from many, including Stroud MP Siobhan Baillie, to calls to move the clock to a museum has demonstrated how uncomfortable so many of us remain in dealing with conversations of race and racism, especially when these are so localised.

These reactions have included sensationalising about ‘cancel culture’ and ‘wiping out history’ and, as our MP described, a concern that ‘a certain minority of people with loud voices have an unquenchable desire to be constantly finding things to be outraged about.’

As unedifying as it is to see an elected MP making such a divisive and bad faith intervention, given that this is a simple case of local people of colour objecting to a racist figure in Stroud, it’s important to try and understand the causes of these reactions if we are to fight against further division.

One thing that is evident across many of these reactions is a sense of fear about the erasure of ‘our’ history. Ostensibly, this is a confusing position given that the calls for the Clock’s removal focus upon its relocation to the Museum in the Park, where the Clock can be viewed by all up close with full context, in contrast to its current plaque. Baillie has since rejected moving the clock to a museum as it would apparently be seen by less people than if it remained overlooking Castle Street. Both a huge disservice to the quality and footfall of the Museum in the Park and a further rejection of the accounts of those impacted by the clock’s presence.

This idea of ‘our’ history being under threat is also evident in Baillie’s complaint to the SNJ’s editor – made when she felt her statement had been taken out of context -, where the concerns of “local people” leading “normal lives” are pitted against a “tiny minority” wanting to “tear down this statue.”

We can see, therefore, a perception of loss, or fear of loss, of ‘our’ history that has been transplanted onto public debates on statues, particularly since the felling of Edward Colston’s statue. What’s more, ‘our’ as it is used here is referring and appealing to those who are not personally offended or affected by the racism embodied in the clock, i.e. White people. Creating a double whammy of exclusion; you should not be offended by this and, if you are, Stroud’s history is not yours to question.

Evidence of this deliberate division can be seen in the current deliberate and sustained attack on the Black Lives Matter movement and affiliate anti-racist groups from the right, despite Baillie saying that is it ‘absolute rubbish’ to suggest she is trying to whip up a culture war. Baillie’s feigned innocence was, however, somewhat undermined this weekend after being personally reminded by the CEO of Kick It Out Tony Burnett, the anti-racism in football group that Baillie continually refers to working with, that her work with Kick It Out “does not give her a free pass to undermine anti-racist groups.”

This isn’t a new phenomenon, rather a new iteration of it. For example, direct links can be drawn to the 1960s and Enoch Powell’s own centering of the “decent, ordinary fellow Englishman”, the idea of a ‘silent majority’ who have lost control of how their country looks and feels, nostalgic for an imagined past that provides an anchor for their sense of self in a rapidly changing world.

This defensive reaction can also be seen in the calls to just ‘move on’, ‘get over it’, or simple non-engagement on the issue despite the harm the Clock has demonstrably caused. Directly contrasting to coverage of Stroud’s unique anti-slavery arch, where discussions and media coverage centred the arch as a local source of pride to be celebrated. The Arch literally being put onto the (Google) map in the wake of the BLM demonstrations last year. Celebrate the good, avoid the bad.

The ignorance running through these reactions is the same that has underpinned and enabled the continual reproduction of Whiteness, and thus racism as a hierarchy of power, since its inception. The clock is seen simply as a depiction of a Black child, free from the context of race that has been so normalised and thus the calls for its moving are preposterous.

When you have people in positions of power, such as Conservative ministers and local MPs such as Baillie, seeking to divide and distract the country through their ‘culture war’, therefore, the wider reaction that we have seen to the idea of moving the clock is entirely predictable.

How we move past this is through building a common understanding of how race and colonialism plays out around us today through honest conversations. Conversations that can be held in and around the Black Boy Clock’s display in a museum, tackling and removing the ignorance that is exploited by those seeking to divide and antagonise.

This is how communities in a rural area like Stroud can answer moments like this with inter-communal learning and solidarity, not sowing further division, and that can lead to a better future for all of us.

If you would like more information on the clock, you can read Stroud District Councils report on it here, and if you want to have your say on the future of the Blackboy Clock, we’d encourage you to take five minutes to fill in Stroud District Council’s public consultation here.

Member discussion