Clothing colonialism: Stroud and the East India Company

By George Thomas and Jamie O’Dell

Much of Stroud’s history is the product of centuries of growth in its textile industry. Fast-flowing rivers in the area’s steep valleys were used to power mills, which turned sheep’s wool into high quality fabric destined for sale in distant parts of the globe. Over the centuries, the town and its mills grew, with canals and railroads gradually constructed between the Five Valleys and beyond to cities such as London, Bristol, and Exeter; connections that continue to serve and benefit the Stroud area today.

The town’s most famous Stroudwater Scarlet broadcloth is instantly recognisable in the military uniforms of the British Empire’s forces, and records show it being traded across the Atlantic in North America and as far east as China. However, one particular business link stands out in its importance in the growth and maintenance of Stroud’s textile industry.

This link was with the British East India Company (EIC), which, after being founded and granted its royal charter in 1600, shipped British goods alongside European military tactics and technologies across the Indian subcontinent and China while shipping profits and loot back to Britain.

The importance of this link for Stroud’s development is hard to overstate. In October 1815 alone the EIC ordered almost £40,000 worth of product from mill owners in the Stroud Valleys; £3,585,018 in today’s money.

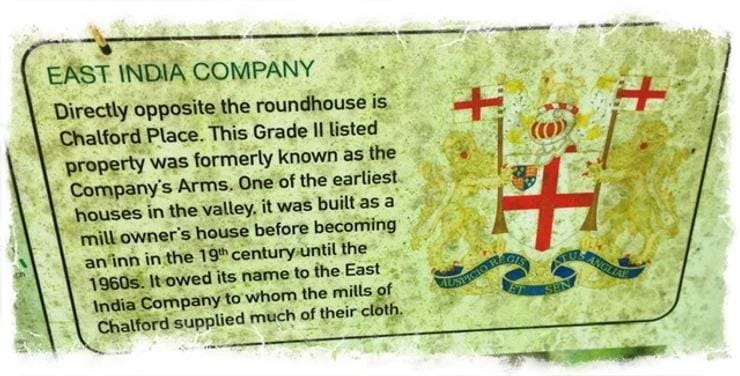

We can also see the importance this had for individual mills, with Longford’s Mill near Minchinhampton – now converted into housing – apparently being the EIC’s largest supplier of cloth in 1820 through fulfilling orders then worth £20,000. Chalford’s mills similarly owed much of their business to the EIC, with Chalford Place previously being known as the Company’s Arms, after the East India Company.

Bolts of broadcloth coloured in Stroud Scarlet and Uley Blue were the commodity with which the region’s wealth was built. It provided the vast quantities of capital necessary for the investments in transport links and new technologies of the industrial age. Similarly to our previous examination of Stroud’s links to the transatlantic slave trade and Caribbean plantations, we can see how the financial gain generated by corporate imperialism flowed directly into the mills and accompanying infrastructure of the Stroud Valleys.

The cost of this transfer of wealth is visible in the reduction of India’s share of the global economy, from 27% in 1700 to just 3% when the British left India in 1948. Examples like this allow us to clearly see how India was governed by the EIC, and subsequently as the ‘jewel in the crown’ of the British Empire, solely for the benefit of Britain and British shareholders by men wearing cloth made, dyed, and paid for in Stroud.

This amounted to the ‘supreme act of corporate violence in world history’ undertaken by the company accountable only to its shareholders with, at its zenith, a standing army of 150,000 men. As one company official observed in the 1840s (just after the peak of Stroud’s engagement with the EIC), as the company absorbed each new state and territory “the little court disappears, trade languishes, the capital decays, the people are impoverished, the Englishman flourishes, and acts like a sponge, drawing up riches from the banks of the Ganges, and squeezing them down upon the banks of the Thames.”

In contrast to the heyday of the EIC and Stroud’s textile industry, the flow of wealth from British colonies into areas like Stroud may now seem to be broadly defunct, a topic for the history books like much of Stroud’s own textile industry. However, while the mechanisms of this flow have indeed changed, the direction of flow fundamentally has not.

Even today, despite the closure or repurposing of Stroud’s mills over the past 100 years, these same structures of violence and economic exploitation – the calling cards of racial capitalism – exist all around us. It is easy to think that because there is no longer a formal British Empire, or that the EIC no longer exists, that these colonial economic structures are also no more.

The continuities in wealth transfer within the Colonial Global Economy continue through a myriad of different mechanisms, such as international investment and arbitration laws, created by countries in the Global North*. These laws and regulations act as instruments of coercion and economic violence against nations in the Global South, enforced by international institutions such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), destabilising their economic and political bases forcing compliance or collapse. Full sovereignty is denied, as any degree of ‘development’ becomes contingent on the demands of market access for foreign Capital.

Our modern garment and textile industry is the perfect example of how, while the patterns of production have seemingly reversed, the flows of wealth have not. The power imbalance in the garment and textile sector globally leaves major brands and retailers, from Nike to Primark, absorbing the lion’s share of the profits while suppliers continually have their prices and production times squeezed. Meanwhile, workers are forced to operate with few protections in often highly intense and precarious labour in order to maintain both the industry’s profitability and our cheap clothing. Additionally, the profits of the industry are also captured by the public purses of the Global North through mechanisms such as VAT, feeding into our public services and welfare systems such as the NHS.

The extent of this colonially-structured power disparity, which is replicated across global supply chains and protects the profits of major brands and retailers while shielding them from the risk, have been painfully evident during the Covid-19 pandemic. In Bangladesh, for example, where the Stroudwater Scarlet coated EIC did so much harm, more than half of garment factories had their in-process or already completed orders cancelled by their buyers. Despite buyers having contractual obligations to pay for these orders, they also, in 71% of cases, refused to pay for the raw materials that had already been purchased by the suppliers. Well over one million workers were subsequently left out of work, often without severance pay.

The details of past and present colonial exploitation outlined here, and Stroud’s own benefiting from it, shouldn’t come as a fundamental surprise. Even before last year’s Black Lives Matter protests, the fact that history’s most brutal and murderous regimes and organisations, such as the EIC and the British Empire, existed as mechanisms of economic exploitation is evident for anyone who casts an honest eye over the matter.

These mechanisms become part of our nation’s material reality, reflected and reproduced in our everyday cultural milieu – building over the centuries like layers of paint on canvas, until the original blood-red brushstrokes are obscured. Therefore it is not the knowledge so much that we lack, but rather the perspective required to come to grips with the challenge of confronting contemporary colonial structures.

Here lies the value of understanding our local and national historical ties to the British Empire; we can begin to recognise the structures that have outlived generations, mutating into the mechanisms we can identify today. From this position of understanding we should take action, both individually and collectively.

As we celebrate Stroudwater Scarlet, as we walk down the canal and past the old or refurbished mills, the inevitable march of time and the physical distance between Stroud and Asia can easily mask the very real links that still connect us. However, these are links that we can learn to recognise and have the capacity to change. As consumers, these links are constituted and our understanding cushioned by access to cheap commodities, produced abroad. However, it is not simply enough that we see this as a consumer issue where people who can afford to shop ethically do so. We must ask ourselves as a society if we are comfortable continuing to live and vote for the same capitalist system that does such harm.

Perhaps rather we can understand that as individuals we are blown by the winds of forces larger and older than ourselves, but in choosing to act in cooperation and for just causes beyond oneself, we can shift the balance of power to create meaningful change in the lives of the most exploited. Not through loans and trade or ‘aid’ in the Global South, but through addressing the legally enshrined colonial power structures maintained by us here in the Global North. This is one way that we can undertake and vote for a more genuine form of international solidarity, rather than choosing to continue to wear the spoil of empire.

This short lecture by Dr Paul Gilbert on the Colonial Global Economy, part of the Connected Sociologies Curriculum Project, outlines these mechanisms in greater detail.

Member discussion